On Being Touched and Touching Strangers. Lessons from Disability Experiences

Have you ever wondered why even well-intentioned touch can feel intrusive? Discover powerful lessons from disability experiences that illuminate how consentful touch can foster genuine connection and trust in everyday life and help you to avoid the opposite.

In a heated exchange in Cannes in May 2025, actor Denzel Washington called out a photographer who forcibly grabbed his arm to take a portrait. In response, Washington firmly set his boundaries, scolded the journalist, and angrily warned the photographer not to touch him again. The incident sparked a debate about the importance of consent and respect when interacting with others, especially when it involves physical contact with a stranger.

The video of the encounter between the photographer and actor is available on YouTube.

Have you ever felt discomfort when a stranger touched you unexpectedly, even if their intention was helpful?

During the COVID-19 pandemic, even a simple handshake suddenly felt perilous, underscoring the complex and nuanced nature of consent surrounding touch.

Nobody likes to be bumped around in the Metro, but we accept it. Still, we try to avoid it.

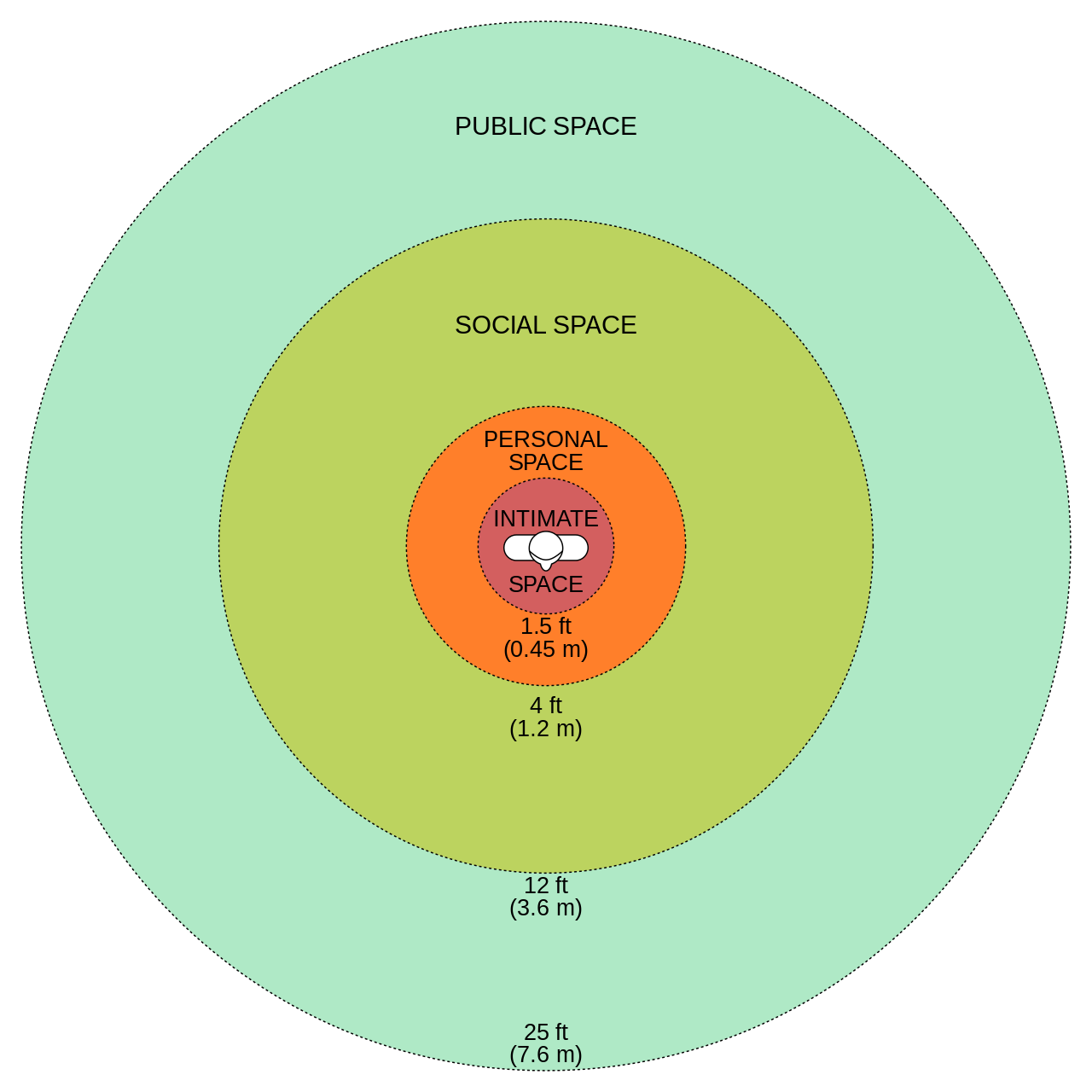

Proxemics and Personal Space

Anthropologist Edward T. Hall introduced the concept of proxemics, studying how humans use space and distance to communicate comfort, intimacy, and boundaries. Hall identified various spatial zones, including intimate, personal, social, and public distances, each representing different levels of comfort and interaction.

Recognising these zones can guide respectful touch and interactions, as crossing these boundaries without consent can create discomfort or even hostility. Understanding proxemics helps us navigate haptic interactions with increased awareness and sensitivity, respecting the invisible yet crucial boundaries that maintain individual dignity and comfort.

For disabled people, being touched in public settings can be an everyday experience.

What we can learn from disability studies and culture

Disabled people, disability activists, and disability scholars provide important insights and nuance to the question of how to touch and how to approach another person’s body, especially when haptic interactions involve touching strangers.

Even when the intention is to catch another person’s attention or provide help, being touched abruptly can feel disrespectful, unsafe, boundary breaking.

Unwanted touch can make us feel harmed, angry, unsafe. Taking these feelings seriously, how can we navigate moments when touching a stranger or being touched by a stranger may be helpful or even necessary?

Touch, Intercorporeality, and the Skin

Philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty emphasizes that our skin is not just a barrier but a profound site of Intercorporeality: our body’s ongoing dialogue with the world and other bodies. Disability experiences reveal both the vulnerability and intimacy inherent in this tactile dialogue. Forced intimacy disrupts this delicate bodily boundary and autonomy, illustrating how our sense of touch profoundly affects our fundamental sense of self and others.

Conversely, Merleau-Ponty also highlights the positive aspects of touch, which can reinforce our sense of connection, empathy, and mutual understanding. A supportive or affectionate touch can create trust, comfort, and reassurance, underscoring the profound potential for positive interactions through touch.

Touching to Help in Public Transport

In public transport, people can sometimes rely on help from others. Help can come from people we know, acquaintances, loved ones, or strangers. Not being helped can feel isolating.

A single parent with a stroller and heavy luggage at a train station can feel disheartened if people do not assist with stepping into the train wagon, which all too often requires climbing steps. Mind the gap!

Feeling that the built world is not designed for your needs, combined with absent support, can be isolating and frustrating (Velho 2023). As such, interactions in public transport, where people assist one another, can compensate for inaccessible infrastructures and strengthen a sense of community and solidarity among people in public spaces. However, help is never seamless, nor free of mistakes and harm.

Forced Intimacy

Imagine being guided abruptly by the elbow through a busy airport security line by a well-intentioned stranger—helpful perhaps, but invasive and uncomfortable.

The conditions under which help occurs matter greatly for how people feel safe and included in public spaces. Blind people and wheelchair users who navigate inaccessible infrastructures have written and talked about the importance of consent when people provide help.

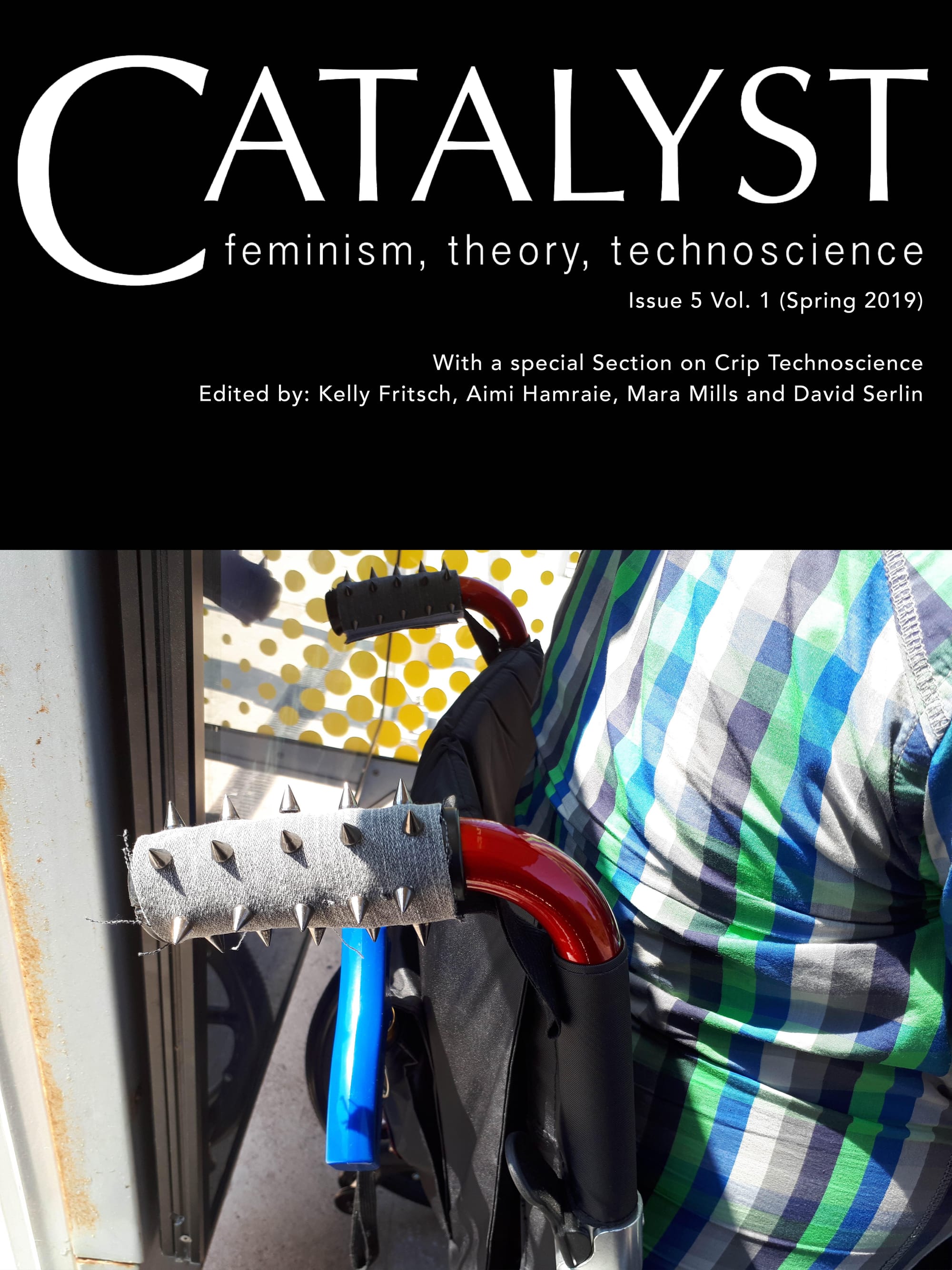

On the cover of the edited volume Crip Technoscience edited by Kelly Fritsch, Aimi Hamraie, Mara Mills, and David Serlin on the journal Catalyst, an invention by John Farnworth comes to mind: push handles of a manual wheelchair with punk-style spikes, communicating: “I do not want to be pushed around”.

Danish activist and politician Sarah Glerup also illustrates uncomfortable forms of touch through her satirical comics, depicting situations where she is forcibly moved in public spaces, such as when cinemas are inaccessible and she must be carried downstairs, causing humiliation. Help in these two examples is frictional, oppositional, and contradictory.

What John and Sarah illustrate through their creative work is what writer and disability justice activist Mia Mingus (2017) calls forced intimacy, defined as:

“Forced Intimacy” is a term I have been using for years to refer to the common, daily experience of disabled people being expected to share personal parts of ourselves to survive in an ableist world. This often takes the form of being expected to share (very) personal information with able bodied people to get basic access, but it also includes forced physical intimacy, especially for those of us who need physical help that often requires touching of our bodies”.

Access Intimacy

Despite potential forced intimacy, more respectful forms of help are constantly emerging. In contrast to forced intimacy, Mia Mingus (2011) describes access intimacy as “the hard to describe feeling when someone else “gets” your access needs.”

For instance, imagine the ease and trust you feel when a friend instinctively knows how to offer support, subtly steadying you when you stumble. With touch in public transport, this intimacy emerges in long-term relationships, such as those between blind persons and their guide dogs or companions, as they learn to anticipate each other’s movements and needs seamlessly.

People with reduced mobility, who rely daily on assistance, also learn to move harmoniously with their companions. Disability experiences thus enhance the capacity to provide supportive, respectful touch, transforming interactions into access intimacy.

COVID-19 and the Relearning of Touch

COVID-19 forced society to renegotiate personal space and boundaries around touch: from hugs at family reunions replaced by awkward elbow taps to navigating supermarkets with new rules of personal space. The pandemic vividly demonstrated the critical need for clear, respectful consent around touch, making disability activists’ longstanding arguments resonate more broadly.

Everyday Touch and Everyday Ethics

Every interaction carries ethical implications, whether assisting someone on public transportation or engaging in social interactions. We’ve all experienced ambiguous scenarios: offering help to someone with heavy groceries, unsure if grabbing their bag would be intrusive or helpful. These everyday interactions reflect broader ethical choices around bodily autonomy, respect, and consent.

Towards Haptic Connections

Disability scholar Akemi Nishida (2022) writes that despite the pervasive desire for independence in contemporary culture, we undeniably thrive as interdependent beings.

Disability reminds us that our needs change over time, as does our capacity to assist others. As such, we share a common history, past and future, where being helped and providing help through touch is essential care.

Children new to public transportation require guidance and handholding. In busy train stations, passengers may request directions or claim space for their bulky luggage. Wheelchair users need ramps, assistance and space to access vehicles and elevators. Indeed, as Daniel Muñoz (2023) reminds us: accessible infrastructures and designs require ongoing labor. Accessibility is thus an ongoing commitment.

Learning from disability experiences and culture helps us imagine new ways of relating to frictional haptic moments as we move together in solidarity. By learning from disability experiences, especially in a post-COVID world where touch has become newly meaningful, we cultivate an ethical sensitivity in everyday interactions.

How we touch each other forms individual dignity and the production of our shared social world.

Good Advice for Respectful Touch:

Returning to Denzel Washington's confrontation in Cannes, we are reminded of the vital importance of consent and respectful boundaries in all interpersonal interactions. Whether in disability contexts, celebrity encounters, or in any other areas of social life, respectful touch ensures dignity, safety, and meaningful connection for everyone. With that said, we list some tips:

- Always obtain explicit consent before initiating physical contact, even if you intend to help.

- Pay attention to verbal and non-verbal cues to ensure the other person is comfortable.

- Avoid abrupt or forceful touch, especially when interacting with strangers.

- Recognize and respect personal boundaries, especially in public spaces.

- Be mindful and patient, understanding that everyone's comfort levels with touch may vary.

- Please educate yourself on respectful ways to assist people with disabilities, prioritizing their autonomy and preferences.

- Remember that gentle, respectful touch can enhance feelings of connection and community.

Barbara and Brian (together with Sara Merlino) are conducting a new research project on accessibility and disability in workplace settings. Read more on the University of Copenhagen’s website.

Works cited:

- Hall, E. T. (1966). The Hidden Dimension. Anchor.

- Merleau-Ponty, M. (2002). Phenomenology of Perception. Routledge.

- Mingus, Mia. 2011. “Access Intimacy: The Missing Link.” Leaving Evidence (blog). May 11, 2011. https://leavingevidence.wordpress.com/2011/05/05/access-intimacy-the-missing-link/.

- ———. 2017. “Forced Intimacy: An Ableist Norm.” Leaving Evidence 6.

- Muñoz, Daniel. 2023. “Accessibility as a ‘Doing’: The Everyday Production of Santiago de Chile’s Public Transport System as an Accessible Infrastructure.” Landscape Research 48 (2): 200–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/01426397.2021.1961701.

- Nishida, Akemi. 2022. Just Care: Messy Entanglements of Disability, Dependency, and Desire. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- Velho, Raquel. 2023. Hacking the Underground: Disability, Infrastructure, and London’s Public Transport System. University of Washington Press.